"Murder on the Orient Express" Reader's Guide

Page 2POIROT AND MARPLE

Agatha Christie created two great detectives. One she loved. One she loathed.

Jane Marple, a nosy spinster in a small village, appeared in twelve novels and twenty short stories. The character was patterned after her step-grandmother. Christie said that both Jane and Gran “always expected the worst of everyone and everything, and were, with almost frightening accuracy, usually proved right.” Over time, several actresses have interpreted Miss Marple, each with a popular following.

Hercule Poirot appeared in twenty-two novels, one play, and over fifty short stories. He appeared in Christie’s first published novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. Written in 1916 and published in 1920, the backdrop of the First World War had a lot to do with explaining why such a brilliant Belgian was out of work and roaming England. At the time, sympathy with German occupied Belgium was also equated with patriotism.

The first description of Poirot reads:

“He was hardly more than five feet four inches but carried himself with great dignity. His head was exactly the shape of an egg, and he always perched it a little on one side. His moustache was very stiff and military. Even if everything on his face was covered, the tips of moustache and the pink-tipped nose would be visible.”

“The neatness of his attire was almost incredible; I believe a speck of dust would have caused him more pain than a bullet wound. Yet this quaint dandified little man who, I was sorry to see, now limped badly, had been in his time one of the most celebrated members of the Belgian police.”

We have to assume that the limp was a war injury because it disappeared in later works. Things that held constant were spotless patent leather shoes with spats, a pince-nez, dark and balding hair, an abiding love of Mozart and Bach, an exceedingly sensitive stomach which prevented overseas travel, extreme punctuality, and a bank balance of 444 pounds, 4 shillings, and 4 pence.

What is always in doubt, and purposefully so, is the man’s background. We’re led to believe that he comes from a large family with little wealth. Other bits of past are sometimes mentioned, but the reader is never sure if it’s the truth, or simply said to encourage others to talk. The detective does have an uncanny ability to get people conversing about their past and feelings. (That will be tested in Orient Express) Poirot prides himself on the order and method of his “little grey cells” which allow him to successfully put those bits into a completed puzzle.

Like Arthur Conan Doyle and his Sherlock Holmes, Christie grew tired of her character. By 1930, she called him “insufferable” and by 1960 “a detestable, bombastic, tiresome, egocentric little creep.” However, unlike Conan Doyle, she never considered a premature death. She felt a responsibility to give the public what they wanted, and they wanted more Poirot.

During the 1950’s, she did write a final book ending with Poirot’s demise. However, she tucked it away in a safe until she knew her abilities to continue his adventures had reached an end. Christie continued writing Poirot mysteries into the 1970’s with her health failing. When it became apparent that she was no longer able to write, the safe was opened, the manuscript given a final revision, and Curtain became the final Poirot story in 1976.

Poirot is the only fictional character to receive an obituary in the New York Times.

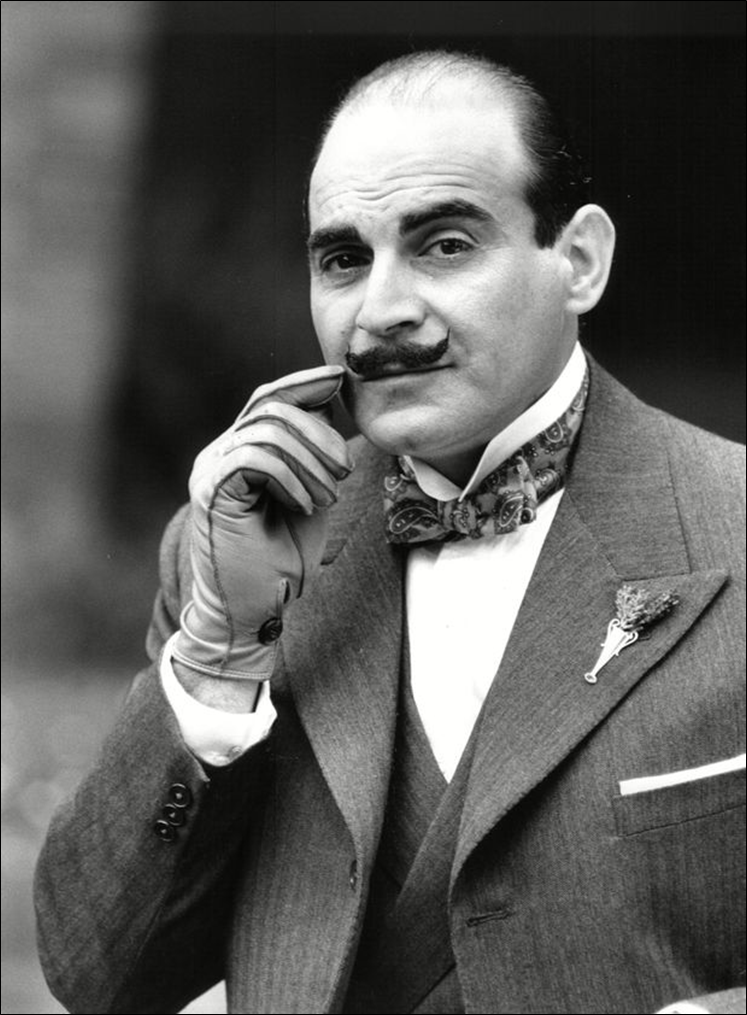

Over the years, many acclaimed actors have portrayed Hercule Poirot such as Austin Trevor, John Moffatt, Albert Finney, Sir Peter Ustinov, Sir Ian Holm, Tony Randall, Alfred Molina, and Orson Welles. It was notable that physically, none of them really fit the description of the character and, arguably, didn’t convincingly fill the detective’s diminutive shoes.

David Suchet C.B.E. became the quintessential Poirot when he took over the role for BBC in 1989. By his retirement in 2013, he had interpreted all of the 33 Poirot novels.