On the Same Page

Reader’s Guide

The Phantom of the Opera

► Gaston Leroux

► Serial Literature

► Paris Opera

► Palais Garnier

► Film Adaptations

► Musical Adaptations

► Discussion Questions

Gaston Leroux

(May 6, 1868 – April 15, 1927)

While official records state that Gaston Louis Alfred Leroux was born in Paris on May 6, 1868, in reality, he was born between train stops leading to Paris on that date. Julien and Marie Leroux were heading into town when Marie’s labor became so intense that the train was stopped, and she was carried to the closest house to give birth. Later in life, Gaston searched out the house and found that it had been converted into an undertaker’s shop. His life began with interesting stories and continued to be full of tales that inspired others.

While official records state that Gaston Louis Alfred Leroux was born in Paris on May 6, 1868, in reality, he was born between train stops leading to Paris on that date. Julien and Marie Leroux were heading into town when Marie’s labor became so intense that the train was stopped, and she was carried to the closest house to give birth. Later in life, Gaston searched out the house and found that it had been converted into an undertaker’s shop. His life began with interesting stories and continued to be full of tales that inspired others.

He was schooled in Normandy and later returned to Paris where he studied law until 1889. In that year, he published his first poem, a sonnet, which planted the desire for further writing. That same year, he also inherited millions of francs when his shipbuilding father passed away. He blew through them quickly with a wild life-style and intense gambling. He was quickly bankrupt and learned from the experience that law was perhaps too boring for his liking. He never completed his studies.

In 1890, he began working for L’Echo de Paris as a court reporter and theatre critic. He later moved to Le Matin where he did his most serious journalistic work. He became an international correspondent covering, among other things, the 1905 Russian revolution, the Fez riots, and Vesuvius eruptions. At home, he also investigated cells below the Paris opera house that had been used to hold political prisoners during the 1871 Paris Commune.

In 1890, he began working for L’Echo de Paris as a court reporter and theatre critic. He later moved to Le Matin where he did his most serious journalistic work. He became an international correspondent covering, among other things, the 1905 Russian revolution, the Fez riots, and Vesuvius eruptions. At home, he also investigated cells below the Paris opera house that had been used to hold political prisoners during the 1871 Paris Commune.

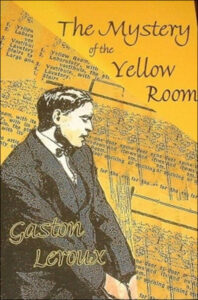

A longtime fan of Edgar Allen Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle, Leroux left journalism in 1907 to turn his hand to fiction, specifically detective stories. Although less well known in English speaking countries, his detective novels might be considered the French equivalent of Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories.  His first novel, published in 1908, was Le mystere dela chamber jaune or The Mystery of the Yellow Room which was serialized in the magazine L’Illustration. The story introduced amateur detective Joseph Rouletabille and began a lengthy series. It is still considered one of the finest examples of a “locked room” mystery. Leroux also wrote another extensive Cheri Bibi series and dozens of stand-alone novels in a wide variety of genres.

His first novel, published in 1908, was Le mystere dela chamber jaune or The Mystery of the Yellow Room which was serialized in the magazine L’Illustration. The story introduced amateur detective Joseph Rouletabille and began a lengthy series. It is still considered one of the finest examples of a “locked room” mystery. Leroux also wrote another extensive Cheri Bibi series and dozens of stand-alone novels in a wide variety of genres.

His most famous novel in English is, of course, The Phantom of the Opera which was released as a serial in 1909-1910 in the Paris daily Le Gaulois and published in book form in 1910. An English translation quickly followed in 1911.

Leroux married Jeanne Cayette in 1917 after his first wife, Marie LeFranc, passed away. The couple had already been living together for a number of years and had two children, Alfred-Gaston and Madeleine.

The highest honor the French bestow for both military and civilian honors is the Chevalier de la Legion de’honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor). Leroux was awarded this prize in 1909.

The highest honor the French bestow for both military and civilian honors is the Chevalier de la Legion de’honneur (Knight of the Legion of Honor). Leroux was awarded this prize in 1909.

He died in Nice, France on April 15, 1927, at age 59 of a urinary tract infection. While in France he is still known widely for his mysteries, he is known almost exclusively in America for The Phantom of the Opera. Until the day he died, Leroux always insisted that there really was an opera phantom.

Serial Literature

Leroux released The Phantom of the Opera as a serial in Le Gaulois between September 23, 1909 to January 8, 1910 before publishing the story in volume form in late March of 1910.

While unusual in our time, many of the most popular authors of the 19th century used magazines and newspapers to make their works available to the public. Installments might stretch over a year or more with authors often responding to the reactions they noted in their readers.

In England, most Victorian novels first appeared in installments. Charles Dickens set the trend with The Pickwick Papers in 1836, and most other writers such as Wilkie Collins and Arthur Conan followed suit.

In England, most Victorian novels first appeared in installments. Charles Dickens set the trend with The Pickwick Papers in 1836, and most other writers such as Wilkie Collins and Arthur Conan followed suit.

In the United States, Henry James, Herman Melville, and Harriet Beecher Stowe chose the same method of publication. In fact, not first being accepted and published in a magazine would lead readers to feel the author to be of lower caliber. Only a second- or third-rate writer would resort to going directly to volume form. In our day, it would be the equivalent of a film going directly to video.

In the United States, Henry James, Herman Melville, and Harriet Beecher Stowe chose the same method of publication. In fact, not first being accepted and published in a magazine would lead readers to feel the author to be of lower caliber. Only a second- or third-rate writer would resort to going directly to volume form. In our day, it would be the equivalent of a film going directly to video.

France did not break from the fashion. Novels by Gustave Flaubert, Eugene Sue, and other major authors appeared in serialization; and  Alexandre Dumas’s great classic works such as The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo were all published in installments.

Alexandre Dumas’s great classic works such as The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo were all published in installments.

While serialization is no longer the norm, there are recent authors who have chosen to explore the form. Some notable examples are:

- Tales of the City by Armistead Maupin published in various San Francisco newspapers

- The Green Mile by Stephen King published in six paperback instalments

- Gentlemen of the Road by Michael Chabon in The New York Times Magazine

- The Bonfire of the Vanities by Thomas Wolfe in Rolling Stone

- The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber in The Guardian

- 44 Scotland Street by Alexander McCall Smith in The Scotsman

Paris Opera

Louis XIV founded the Academie Royal de Musique in 1669. Through the centuries and many, many name changes, it has remained the premier organization for classical music and dance in France.

Louis XIV founded the Academie Royal de Musique in 1669. Through the centuries and many, many name changes, it has remained the premier organization for classical music and dance in France.

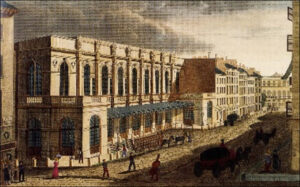

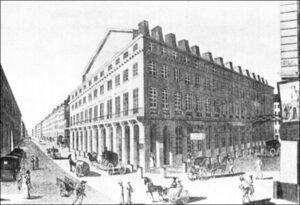

The company has been housed in several buildings over time such as the Salle Le Peletier at left and the

The company has been housed in several buildings over time such as the Salle Le Peletier at left and the  Theatre des Arts at right, but is most closely associated with the Palais Garnier which opened in 1875. Today performances are split between Palais Garnier and the modern Opera Bastille.

Theatre des Arts at right, but is most closely associated with the Palais Garnier which opened in 1875. Today performances are split between Palais Garnier and the modern Opera Bastille.

Opera National de Paris has a current annual budget of roughly 200 million euros supporting a huge permanent staff including 170 musicians, 110 chorus members, and 150 dancers not to mention carpenters, seamstresses, hair dressers, upholsterers, artists, prop specialists, etc. The company gives approximately 380 performances each year with a 94 percent seat occupancy.

Palais Garnier

This 1,979 seat opera house was constructed by Charles Garnier at the request of Emperor Napoleon III in what Garnier described as a Napoleon III style which seems to mean that no surface was left unadorned.

From Scribner’s Magazine 1879:

From Scribner’s Magazine 1879:

The site of the Opera House was chosen in 1861. It was determined to lay the foundation exceptionally deep and strong. It was well known that water would be met with, but it was impossible to foresee at what depth or in what quantity it would be found. Exceptional depth also was necessary, as the stage arrangements were to be such as to admit a scene fifty feet high to be lowered on its frame. It was therefore necessary to lay a foundation in a soil soaked with water which should be sufficiently solid to sustain a weight of 22,000,000 pounds, and at the same time to be perfectly dry, as the cellars were intended for the storage of scenery and properties. While the work was in progress, the excavation was kept free from water by means of eight pumps, worked by steam power, and in operation, without interruption, day and night, from March second to October thirteenth. The floor of the cellar was covered with a layer of concrete, then with two coats of cements, another layer of concrete and a coat of bitumen.

The wall includes an outer wall built as a coffer-dam, a brick wall, a coat of cement, and a wall proper, a little over a yard thick. After all this was done the whole was filled with water, in order that the fluid, by penetrating into the most minute interstices, might deposit a sediment which would close them more surely and perfectly than it would be possible to do by hand. Twelve years elapsed before the completion of the building, and during that time it was demonstrated that the precautions taken secured absolute impermeability and solidity.

Stone for the opera house was quarried in Sweden, Scotland, Italy, Algeria, Finland, Spain, Belgium, and France as Garnier wanted a variety of color for a theatrical effect. While the exterior was being built, the entire opera house was enclosed by a wooden shell which was taken down in 1867 as interior construction continued.

Stone for the opera house was quarried in Sweden, Scotland, Italy, Algeria, Finland, Spain, Belgium, and France as Garnier wanted a variety of color for a theatrical effect. While the exterior was being built, the entire opera house was enclosed by a wooden shell which was taken down in 1867 as interior construction continued.

One of France’s series of revolutions halted the building process in late 1870 and early 1871 as the Paris Commune used the facility as a storehouse and prison. Damage, fortunately, was slight.

Besides the opera hall proper, there are vast public chambers. Halls were designed as waiting areas for servants as well as places to wait for carriages which were able to deliver and pick up audience members inside the opera house. Back stage, there were places for 538 people to change, 100 instrument closets, and warm up areas for musicians, singers and dancers.

Somewhere between public and private is the foyer de la danse. Anyone subscribing to at least three performances per week was allowed here between acts to pay their compliments to the ballet corps and watch them practice. The well-appointed space had velvet covered bars and the same slope as the stage.

Somewhere between public and private is the foyer de la danse. Anyone subscribing to at least three performances per week was allowed here between acts to pay their compliments to the ballet corps and watch them practice. The well-appointed space had velvet covered bars and the same slope as the stage.

The opera house has 2531 doors, fourteen furnaces, and over sixteen miles of gas pipes.

Since its original construction three railway lines have been added below the Palais Garnier, one on top of another.

BOX 5

BOX 5

The phantom’s preferred seating area, box 5, is the first box on the first tier of balconies stage right. The box bears a plaque noting its importance, “Lodge of the Phantom of the Opera.”

THE CHANDELIER

THE CHANDELIER

The Palais Garnier does have a gigantic chandelier and it has fallen. The bronze and crystal fixture hanging over the audience seating weighs seven tons and was the center of a disaster on May 20, 1896. During a performance of, appropriately, Floquet’s opera Helle, (although Helle in this instance refers to the name of a Greek princess) a fire broke out in the ceiling over the auditorium. It appears that it began with electrical wires that ran along the wrist-width cables holding the gargantuan lighting fixture up. The cables melted, and the chandelier fell taking girders with it. Miraculously, only one person was killed, but injuries were widespread and severe.

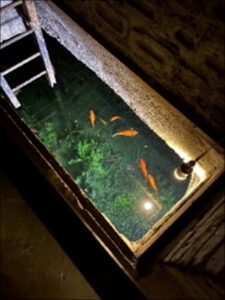

THE LAKE

THE LAKE

There is definitely a lake under the  Paris opera house though it’s considerably less picturesque and romantic as you might imagine from reading the book or viewing any of the adaptations of the novel. Somehow, there are fish which are fed by members of the staff, but there are no boats, hidden lairs with organs, etc.

Paris opera house though it’s considerably less picturesque and romantic as you might imagine from reading the book or viewing any of the adaptations of the novel. Somehow, there are fish which are fed by members of the staff, but there are no boats, hidden lairs with organs, etc.  The only people who regularly visit it are Paris emergency personnel for their dark underwater training.

The only people who regularly visit it are Paris emergency personnel for their dark underwater training.

Film Adaptations

There have been countless films over the past century based, often loosely, on Leroux’s novel. The International Movie Database (IMDB) lists these as critic’s top ten:

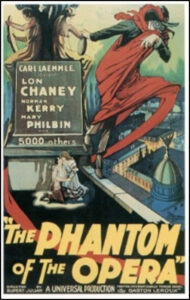

1925 The Phantom of the Opera starring Lon Chaney

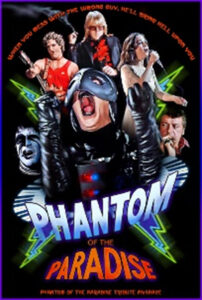

1925 The Phantom of the Opera starring Lon Chaney- 1974 Phantom of the Paradise – contemporary setting with comic elements starring Paul Williams

1989 Phantom of the Opera – goriest version

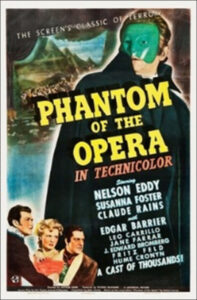

1989 Phantom of the Opera – goriest version- 1943 Phantom of the Opera starring Claude Rains

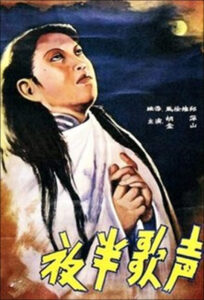

- 1995 The Phantom Lover – set in China

- 2004 The Phantom of the Opera – Andrew Lloyd Weber musical starring Gerard Butler

1962 The Phantom of the Opera starring Herbert Lom

1962 The Phantom of the Opera starring Herbert Lom- 1998 The Phantom of the Opera – this phantom was raised by rats

- 1990 The Phantom of the Opera starring Teri Polo

- 1935 Song at Midnight – China’s first horror film

Though there is some variation in the list from different sources, every “best Phantom” list puts the 1925 silent movie starring Lon Chaney in the top spot.

Though there is some variation in the list from different sources, every “best Phantom” list puts the 1925 silent movie starring Lon Chaney in the top spot.

While it follows the novel most closely, there are major changes. For example, the Persian, a main character in the novel, was replaced by a police detective. The Phantom never studied in Persia but instead escaped from “Devil’s Island.” The Phantom does not die of a broken heart but is instead pursued and killed by a mob.

Filming of this classic was troubled. Universal Studios favored director Rupert Julian was put in charge of the project, and it quickly became apparent that his reputation was undeserved. With many questionable choices, friction on the set was thick. Eventually, Julian and his star stopped speaking to each other. Julian would give Chaney directions through the photographer, Charles Van Enger, to which Chaney would reply, “Tell him to go to h—,” and then do whatever he wanted.

Filming of this classic was troubled. Universal Studios favored director Rupert Julian was put in charge of the project, and it quickly became apparent that his reputation was undeserved. With many questionable choices, friction on the set was thick. Eventually, Julian and his star stopped speaking to each other. Julian would give Chaney directions through the photographer, Charles Van Enger, to which Chaney would reply, “Tell him to go to h—,” and then do whatever he wanted.

It’s unclear whether Rupert Julian was fired or quit, but Universal had to bring in unnamed staff from their western unit to salvage the film.

Lon Chaney took on the role of Erik. Known as “The Man with a Thousand Faces,” Chaney was a master of theatrical makeup. His depiction of the phantom is by far the closest of any to Leroux’s “death’s head” description. (We aren’t including a photo here. When he was first unmasked in the film showings, people screamed and fainted in horror. Since we’ll be showing this film with original organ accompaniment as our final program for this series, we don’t want to steal that moment from you.) The effect was accomplished with a built-up forehead, small wires (ouch) to pull his nostrils up and back, and lots of makeup.

Lon Chaney took on the role of Erik. Known as “The Man with a Thousand Faces,” Chaney was a master of theatrical makeup. His depiction of the phantom is by far the closest of any to Leroux’s “death’s head” description. (We aren’t including a photo here. When he was first unmasked in the film showings, people screamed and fainted in horror. Since we’ll be showing this film with original organ accompaniment as our final program for this series, we don’t want to steal that moment from you.) The effect was accomplished with a built-up forehead, small wires (ouch) to pull his nostrils up and back, and lots of makeup.

Musical Adaptations

Mention a musical adaptation of Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera and almost everyone will think of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s 1986 staging which later became a major motion picture. It was not the first musical based on the novel, nor was it the last.

Mention a musical adaptation of Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera and almost everyone will think of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s 1986 staging which later became a major motion picture. It was not the first musical based on the novel, nor was it the last.

In 1976, Kenneth Hill created the first of the Phantom musicals which premiered in Lancaster, England. Hill wrote the book and lyrics which he set to the music of Verdi, Offenbach, Mozart, Gounod, Weber, Boito, and Donizetti.

In 1976, Kenneth Hill created the first of the Phantom musicals which premiered in Lancaster, England. Hill wrote the book and lyrics which he set to the music of Verdi, Offenbach, Mozart, Gounod, Weber, Boito, and Donizetti.

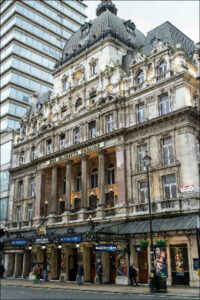

It was this production that first inspired Webber to create his own version having been longing for some time to create something sweepingly romantic. In 1984, he approached Cameron Mackintosh, a frequent producer of Webber’s work, about the possibility. Together, they studied the 1925 film with Lon Chaney and the 1943 film with Claude Rains but had difficulty seeing how they could translate the story to stage. Later, Webber found an out-of-print copy of the Leroux novel in a used bookstore and found the pieces to the puzzle that he was missing. Alan Jay Lerner (My Fair Lady, Camelot, Brigadoon, etc.) was the first lyricist but became ill and was eventually replaced by Charles Hart. The play premiered under the direction of Hal Prince at Her Majesty’s Theatre in London’s West End.

copy of the Leroux novel in a used bookstore and found the pieces to the puzzle that he was missing. Alan Jay Lerner (My Fair Lady, Camelot, Brigadoon, etc.) was the first lyricist but became ill and was eventually replaced by Charles Hart. The play premiered under the direction of Hal Prince at Her Majesty’s Theatre in London’s West End.

The characters stayed with Webber and he wanted to continue the story. He began working with Frederick Forsyth to create an original but related story taking place ten years after the conclusion of the original tale and involving Christine’s son. Their visions for the production diverged. Forsyth continued his version with a novel, Phantom of Manhattan, published in 1999.

The characters stayed with Webber and he wanted to continue the story. He began working with Frederick Forsyth to create an original but related story taking place ten years after the conclusion of the original tale and involving Christine’s son. Their visions for the production diverged. Forsyth continued his version with a novel, Phantom of Manhattan, published in 1999.  Webber unveiled his production of Love Never Dies in 2010. The production was delayed because his kitten, Otto, was playing on Webber’s high-tech electric piano deleted the entire score from the Clavinova. Nothing could be recovered, and Webber had to begin piecing the work back together from memory.

Webber unveiled his production of Love Never Dies in 2010. The production was delayed because his kitten, Otto, was playing on Webber’s high-tech electric piano deleted the entire score from the Clavinova. Nothing could be recovered, and Webber had to begin piecing the work back together from memory.

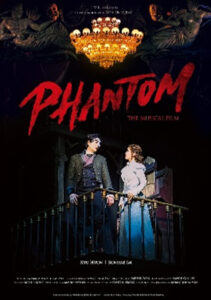

The latest musical based on Leroux’s novel premiered in Houston in 1991, and is simply titled Phantom with music and lyrics by Maury Yeston and a book by Arthur Kopit. Widely produced, the musical seems to be particularly popular in Korea where it was made into a film in 2021.

The latest musical based on Leroux’s novel premiered in Houston in 1991, and is simply titled Phantom with music and lyrics by Maury Yeston and a book by Arthur Kopit. Widely produced, the musical seems to be particularly popular in Korea where it was made into a film in 2021.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

– Do you consider Erik to be more creative or destructive?

– Christine may be musically talented but does not seem to be very astute. How does Erik gain her confidence and manipulate her? How is he able to do it for so long? Do you find any parts of their relationship attractive?

– Why does Erik ultimately let Christine go with Raoul? Does this redeem him in your eyes?

– Is the Persian responsible in any way for the tragedies that take place? What could he have done to prevent them?

– Does it bother you that Leroux never gives the Persian a name?

– How do any of the characters, if at all, grow throughout the story?

– We think of Erik as an outcast forced to live underground, yet he regularly has a woman with him in box 5. Who is this unseen woman? Is he truly the outcast he makes out?

Download the Reader’s Guide

(PDF Download)

Regular Hours of Operation

- Monday: 9:00 am – 6:00 pm

- Tuesday - Wednesday: 9:00 am – 8:00 pm

- Thursday: 11:00 am – 8:00 pm

- Friday: 10:00 am – 6:00 pm

- Saturday: 10:00 am – 2:00 pm

- Sunday: CLOSED

Closures in 2025

- January 1 – New Year’s Day

- January 20 – Martin Luther King, Jr., Day

- February 17 – Presidents Day

- March 28 – Staff Development Day

- April 5 – Building Maintenance

- May 24-26 – Memorial Day

- June 19 – Juneteenth

- July 4 – Independence Day

- August 30-September 1 – Labor Day

- September 19 – Staff Development Day

- October 4 – Building Maintenance

- October 31 – Open from 9:00 am to 6:00 pm

- November 11 – Veterans Day

- November 26 – Closing at 5:00 pm

- November 27-29 – Thanksgiving

- December 24-26 – Christmas

- December 31 – New Year’s Eve

- January 1, 2026 – New Year’s Day

Address

73 North Center

Rexburg, Idaho 83440

We are located on Center Street, just north of Main Street, by the Historic Rexburg Tabernacle.

Contact Us

(208) 356-3461

24 Hour Phone Renewal: (208) 356-6658

askmadisonlibrary@madisonlib.org